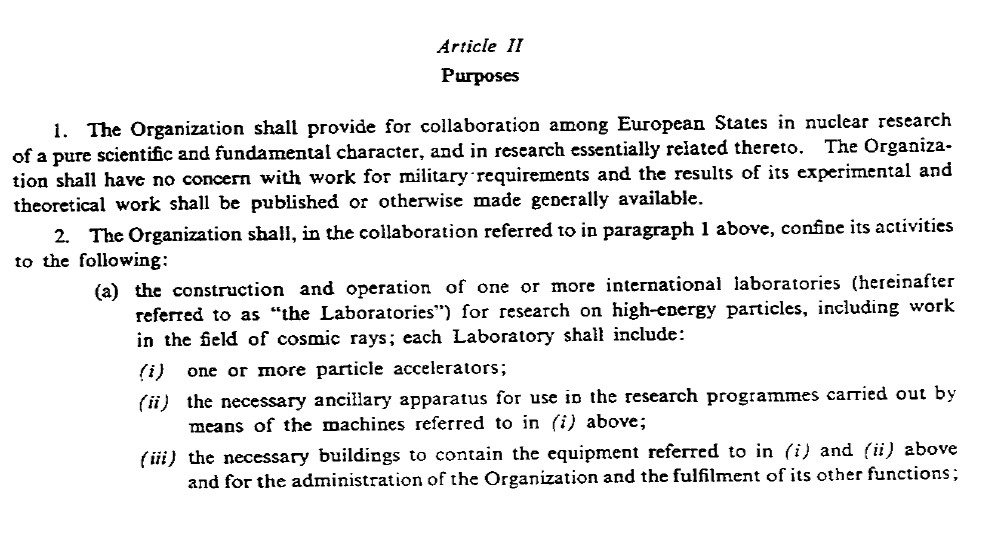

The values of open science have always been at the heart of CERN’s mission, ever since the Organization’s inception. The CERN Convention, signed at UNESCO in 1953, states that “the results of [CERN]’s experimental and theoretical work shall be published or otherwise made generally available.” Empowered by this early mandate, the research community at CERN has been at the forefront of global open science throughout the Organization’s seventy-year history, engaging in “open science” well before the term was even created and setting an example for other scientific domains.

Science, by nature, requires open communication and collaboration in order to progress. Open science makes scientific research more accessible, transparent and efficient, benefiting both the scientific community and society as a whole. It involves openly sharing research output, including by providing open access to publications, making data available and reusable and applying open-source principles to software and hardware. In addition, open science focuses on driving a cultural change in scientific practice to ensure that knowledge creation is inclusive, sustainable and fair.

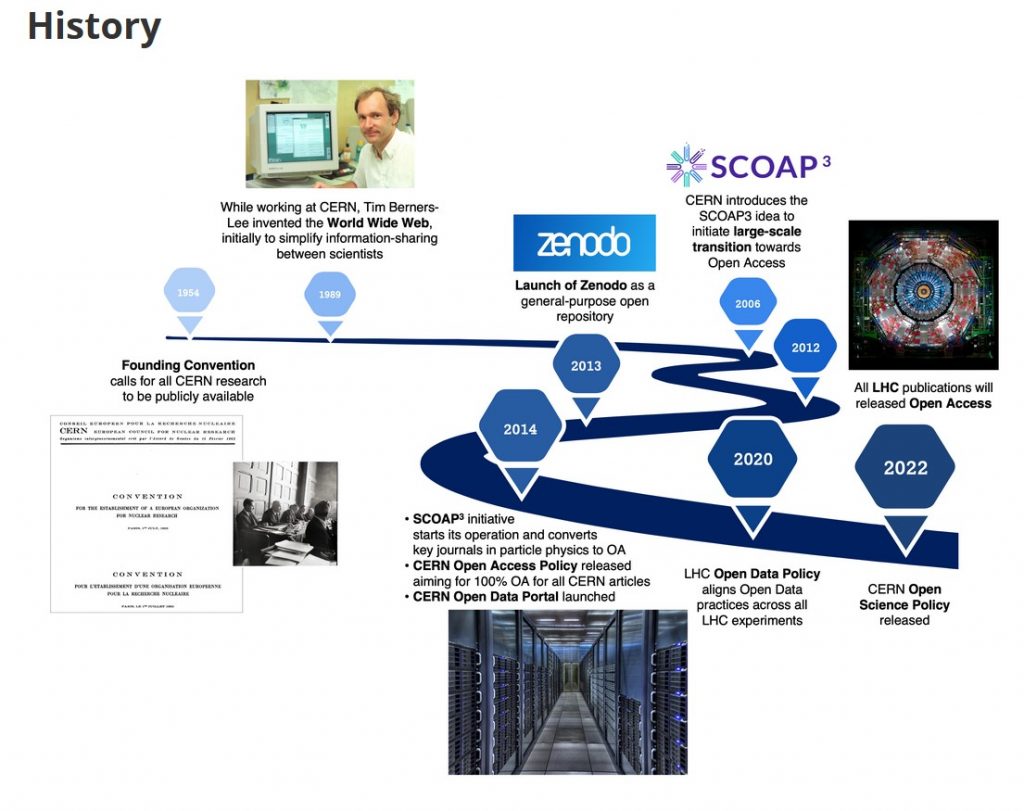

Open science initiatives at CERN have extended well beyond the activities of the Laboratory. Undoubtedly the most impactful of these examples is the World Wide Web, created by Tim Berners-Lee in 1989, initially to simplify the sharing of information between scientists. In 1993, CERN released its source code into the public domain for anyone in the world to share and use freely. As well as its global transformative impact, access to the web heralded a new era for open science, allowing more rapid and broader sharing of results. This spawned the open access movement, which recognised the web’s potential to democratise and share scientific research for the benefit of science and society.

Mindful of this opportunity, the particle physics community harnessed the open spirit of CERN’s collaborations to coordinate a global effort in favour of open access to particle physics research. In 2014, during Rolf Heuer’s term as CERN Director-General, the Sponsoring Consortium for Open Access Publishing in Particle Physics (SCOAP3) was established. A global collaboration of more than 3000 libraries, research agencies and funders from 48 countries, its mission is to enable barrier-free open access, without any fees for readers or authors. SCOAP3 has been key to achieving the objectives of the CERN Open Access Policy, which, since 2014, has required open access publishing of all CERN research papers.

Another flagship open science programme launched by CERN, the Zenodo service, began in 2013, initially as a repository for open source code, but over the past ten years it has grown to be the world’s largest multidisciplinary research repository. It now hosts more than 4 million research outputs and is used in more than 160 countries. The CERN Open Data Portal, which was also launched in 2014, provides unrestricted access to data taken at CERN experiments in order to support outreach and educational efforts, and is used by particle physicists worldwide. In 2020, these efforts were formalised with the publication of CERN’s Open Data Policy.

These efforts, along with other bottom-up open science initiatives, have helped to improve the accessibility, reproducibility and transparency of the research done at CERN. In 2022, to formalise them at the organisational level, CERN published its first Open Science Policy. Encompassing the existing policies for open access and open data, the policy brought together other existing elements of open science – open source software and hardware, research integrity and open infrastructure and research assessment, as well as training, outreach and citizen science. This policy, together with the new CERN Open Source Programme Office and the CERN Open Science Office, supports the research community in these vital areas of practice.

The CERN and Society Foundation (CSF), created in 2014, has also been a key player in CERN’s open science endeavours. By funding knowledge transfer and strengthening links between CERN and the public, it aims to make CERN’s science and technology fully transparent and to share them with society.

The Open Science Policy and the CSF serve to help the scientific community at CERN to understand and continue CERN’s legacy of open science.

Recollections

People talk about CERN not only because of the science we do, but also because CERN is a model for cooperation and collaboration. Our open science projects […] are in essence all about collaboration.

Rolf-Dieter Heuer

Rolf-Dieter Heuer came to CERN in 1984 to work for the OPAL collaboration at the Large Electron-Positron Collider (LEP) and became the collaboration’s spokesperson in 1994. In 1998, he left CERN to take up a professorship at the University of Hamburg, and in 2004 he became research director for particle and astroparticle physics at DESY. He was Director-General of CERN from 2009 to 2015, during which time open science flourished at the Laboratory.

“When I was CERN Director-General, it was already a time of open data and this developed into open science. At CERN, for example, we were wondering what to do with data from former experiments. How should we store it so that we could reuse it? You might ask why we want to reuse data. Well, science develops and other viewpoints emerge, other views on the analysis. So, you need to have access to the old data.

And, by making this data available to the general public, we wanted to inspire trust in science, we wanted people to understand how science works – it was important back then, and is even more important nowadays. Openness, transparency and trust, these are important values that are part of the CERN genes.

Actually, I must admit that, at first, I had some hesitation about making the particle physics data available, because I didn’t know at what point we should make it available and how the general public would be able to analyse it. I feared that we would get eccentric results and have to fight against rumours and fake news. But we did it, and it is a good example of CERN being at the forefront of science and of other developments in the interests of society.

But, as I said, it was not only open data that was on the up. The same wind was blowing from different places: from the European Commission, from CERN, from scientists… It was the right moment and the right atmosphere to open up, to put it bluntly, to open science in general – so open data, but also open source and open access.

Zenodo was launched in 2013 in this spirit. This project of open access was commissioned by the European Commission to support their open data policy, and CERN made it possible. SCOAP3, which converted key journals in the field of high-energy physics to open access, also started operation in 2014. At the time, there was strong hesitation from the American Physical Society and from certain publishers, because they feared it was threatening their business model.

I had the opportunity to meet the chairman of Elsevier, in a small meeting room at Munich airport. It was a very positive discussion and I think he was onboard after that meeting. You have to have a real connection, to meet people. I think the discussion with Elsevier in Munich helped to unlock the other publishers, because we managed to convince them that we didn’t want to take something away from them.

What we wanted was openness for society in high-energy physics, and of course to reduce the costs and keep them as stable as possible – this is what we achieved, as the fee per article hasn’t changed since 2014.

All this was possible because, in high-energy physics, people are collaborating, they have to collaborate. So even if it may sometimes seem like a disadvantage to work with so many people, it is also a big advantage to have many people together, joining forces.

This is why people talk about CERN, not only because of the science we do, but also because CERN is a model for cooperation, for collaboration, and our open science projects like Zenodo, SCOAP3, etc, are in essence all about collaboration.”

For more information about open science at CERN, go to openscience.cern. Rolf-Dieter Heuer speaks about his role in the creation of the CERN and Society Foundation in this recent CERN Courier viewpoint.