In 1989, Tim Berners-Lee, a young scientist working at CERN, wrote a proposal for an information management system based on the Internet. At the time, few people really understood the significance of his seemingly abstract idea. Luckily, however, his supervisor and a few colleagues had the foresight to let him work on an invention that would change the world.

By the late 1980s, the Internet was already an invaluable tool for scientists. It allowed them to communicate by email, log in to powerful computers remotely and exchange information via a set of complex instructions. But the system was used only by academics who knew where to send their query.

CERN was a particularly fertile ground for developing a more efficient information-sharing system. The Laboratory already had a long tradition of computing and networking. Thousands of scientists from institutes all over the world were working there together, using a variety of computer systems and languages. The proliferation of standards, programming languages and incompatible computers, and the dispersal of information and scientists, made it more crucial than ever to set up an effective system for sharing information.

As a consultant in the early 1980s, Berners-Lee had already developed, for his own use, a system that gathered information without the need to glean it from scientists. Returning to CERN a few years later, he soon realised that a more global solution was needed to overcome incompatibilities and that it must be completely decentralised: the information would not have to be replicated in multiple databases, and the connections between computers would create a much more powerful global database.

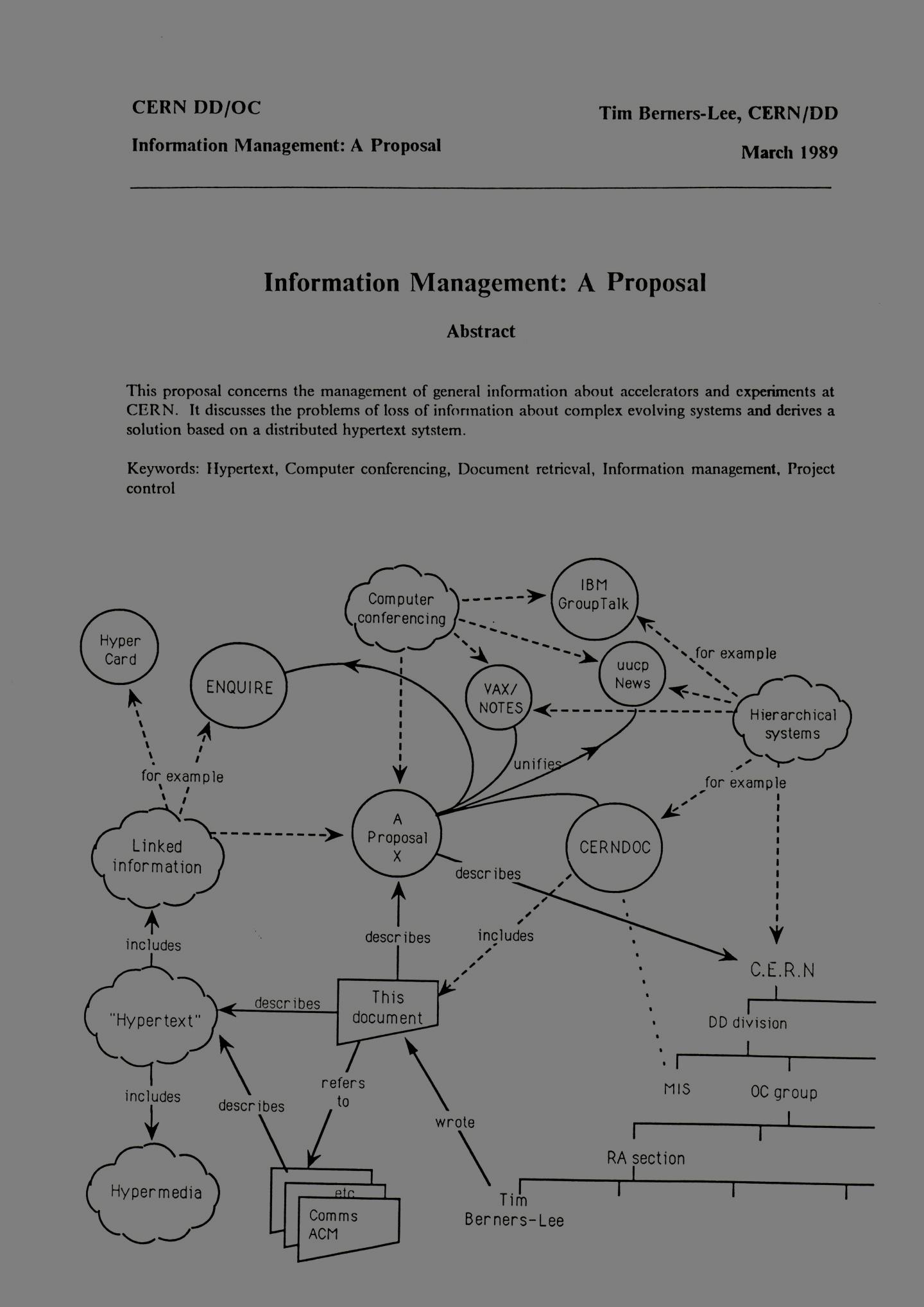

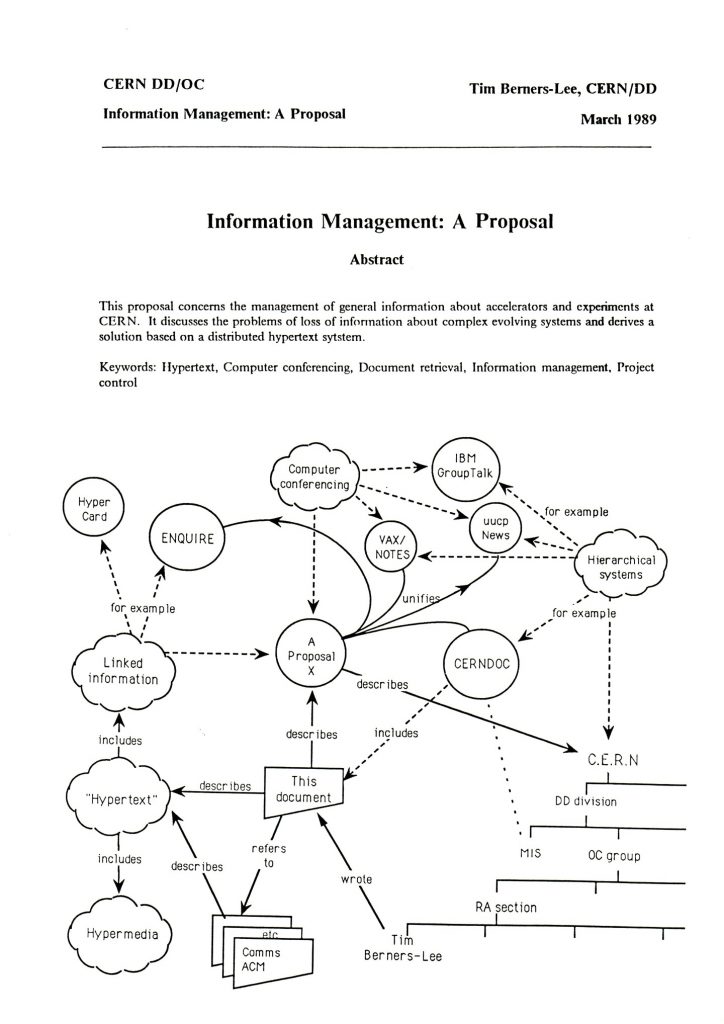

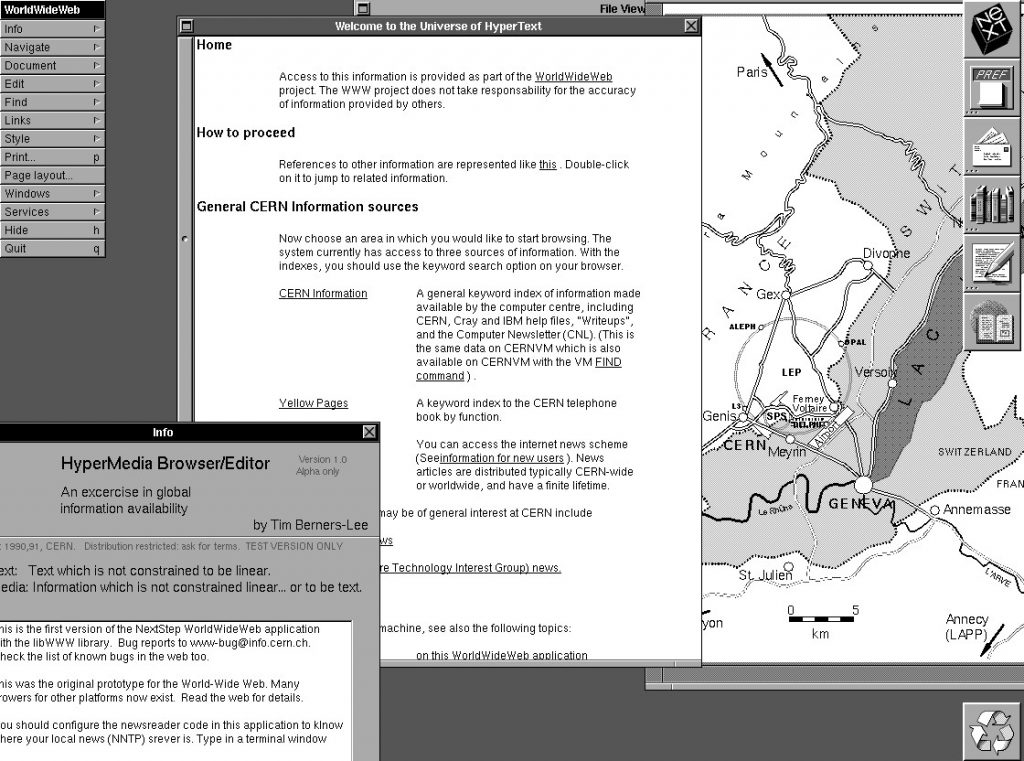

From this idea, Berners-Lee’s great inspiration was to create something entirely new by combining a physical network, the Internet, with the concept of hypertext, invented in the 1960s, which made it possible to create links between one document and another by “pointing-clicking”. He developed html (HyperText Markup Language) to display pages, the url (Uniform Resource Locator) address system to identify them and the http (HyperText Transfer Protocol) to link them together via the Internet. He wrote his first proposal for the World Wide Web in March 1989 and his second proposal in May 1990, which was formalised as a management proposal in November 1990. By the end of 1990, the first Web server and browser were up and running at CERN. The first website explained the concept of the Web. From this primitive network, the Web steadily grew to include all the major particle institutes around the world.

The Web was not the only information-sharing system being developed for the Internet. There were others, notably “Gopher”, developed at the University of Minnesota. But something happened in 1993. The University of Minnesota decided to stop distributing Gopher servers free of charge. Immediately, Berners-Lee encouraged CERN’s management to take the important decision to place the Web in the public domain, thereby ensuring that it would forever be free. From then on, the Web grew exponentially.

In 1994, Berners-Lee left CERN to found and become director of the World Wide Web consortium, the industry-neutral forum for the development of Web technology. The same year, CERN hosted the first International Conference on the World Wide Web, which was dubbed the “Woodstock of the Web”.

Today, hundreds of millions of active web servers around the world are visited by billions of users. For many, life without it would be unthinkable, and honours have been awarded to its inventor – now Sir Tim Berners-Lee.

Recollections

My March 1989 Web proposal was when I put a stake in the ground and said we have to do that. From then on, it was just a question of getting it to work.

Tim Berners-Lee

I arrived at CERN in 1980 with a bunch of programmers on a six-month contract. We were brought in to work on the Proton Synchrotron Booster as they were replacing a wonderfully retro, sci-fi control room, full of valves, trackballs and gadgets, with far less beautiful computers. We were working in temporary portacabins, but we got to know CERN and to know Geneva. It was an amazing place to be. We were dropped into this environment where you had to find out which software to write, what hardware it connected to and who were the people responsible, so I ended up making a command-line programme called ENQUIRE to pull together data that was spread over different documentation systems. Once the six-month contract was over, I returned to the UK.

A physicist friend of mine later recommended a CERN fellowship, which involved helping experiment communications between the surface and the pit. Each experiment involved people from different countries who’d arrive with a variety of different hardware, with documents stored on completely different systems and everyone writing their own programmes. It was a creative space, full of early adopters.

My March 1989 Web proposal was when I put a stake in the ground and said we have to do that. From then on, it was just a question of getting it to work. At that time, there were committees for new experiments, but not for making global hypertext systems. So I had to work on it alongside my tasks, but my group leader, Mike Sendall, agreed to buy a NeXT machine and told me that I could kick the tyres. With a wink he said “you’ll need to develop something with it”.

At the time, despite physicists having computers on their desks, the main reason they’d log into the mainframe was to access the phonebook. This was key. The phonebook web server made the Web useful at CERN. I’m sure that for years many people at CERN only used the Web for the phonebook!

In 1993, CERN agreed to make the Web royalty-free. That was crucial. Then, in 1994, I went to MIT and used their experience of leading similar consortiums to help establish the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C). CERN did the right thing – people could come to the Web knowing that it was going to be free. Otherwise, it would have been just another commercial system competing with many others, and we wouldn’t be talking about it now!

Sir Tim Berners-Lee took part in the CERN70 public event “An extraordinary human endeavour” in May 2024. Watch the recording here.